As the Roman Republic crumbled under civil war and political corruption, one man chose death over submission. His name was Cato the Younger, and his story still echoes today, in philosophy, in history, and in our modern political dilemmas.

If you’ve already watched the video on this story, here you’ll find a deeper historical dive, Stoic context, and reflections on why Cato’s final act matters now more than ever.

Who Was Cato the Younger?

Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis, known as Cato the Younger, was a Roman senator, statesman, and devout follower of Stoic philosophy. Born into a prominent family, he inherited the legacy of his great-grandfather, Cato the Elder, and carried that tradition of virtue, discipline, and unwavering commitment to the Republic.

Unlike many of his peers, Cato refused luxury, rejected bribes, and lived modestly. He believed that power should be earned by character, not ambition.

The Political Crisis of Rome

By the first century BC, the Roman Republic was falling apart. Corruption plagued the Senate, civil wars shattered stability, and generals like Julius Caesar rose in popularity by defying constitutional limits. While others accepted Caesar’s promises of order and prosperity, Cato saw a threat to the Republic’s core values, liberty, law, and checks on power.

Cato openly opposed Caesar at every turn. He debated him in the Senate, blocked his policies, and warned that a single ruler, even a brilliant one, was incompatible with a free Republic.

Cato’s Final Stand in Utica

After Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49 BC and ignited civil war, Cato joined the last defenders of the Republic. But their cause was doomed. One by one, Republican cities fell. Friends and allies surrendered. Even Cicero eventually gave up hope.

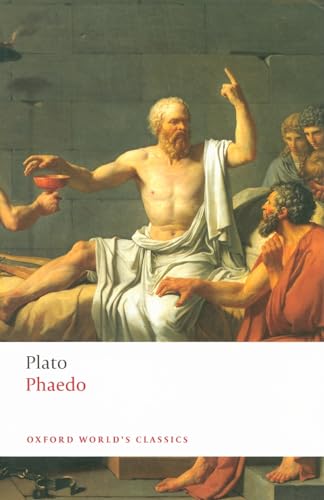

Cato fled to North Africa and took refuge in Utica. There, he evacuated civilians, settled public finances, and ensured the safety of his allies. Then, alone, he read Plato’s Phaedo—a dialogue on the death of Socrates—and took his own life.

His suicide was not an act of despair. It was a final, Stoic act of autonomy. To Cato, living under a tyrant, even a merciful one, was unacceptable. Death was not defeat, but the last protest of a free man.

Cato and Stoicism

Cato’s life is one of the clearest historical examples of Stoic philosophy in action. He believed in virtue, duty, and the moral strength of the individual. For Stoics, freedom is not the absence of pain, but the ability to live in accordance with reason and principle, even when the cost is high.

Cato’s calm in the face of death reflected a deeper belief: that no external force, not even Caesar himself, could rule over a truly free mind.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

Cato’s defiance did not die with him. During the Enlightenment, he was rediscovered as a symbol of moral resistance. George Washington even had a play about Cato performed at Valley Forge to inspire his troops during the American Revolution.

To many thinkers, Cato represents a timeless warning: Democracies fall not just through violence, but through silence. When ambition overrides law, and comfort outweighs principle, freedom erodes.

In a time of rising authoritarianism, political polarization, and institutional decay, the story of Cato the Younger offers a question that remains painfully relevant:

What matters more, survival or principle?